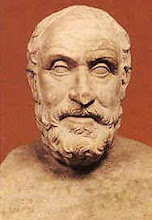

Yesterday I read a paper by the philosopher George E. Moore (pictured) called A Defense of Common Sense (full text). In the paper, Moore explains his view of the universe and talks about why he believes in the concept of common sense rather than extreme skepticism. Though Moore is an eminent philosopher and I am sure there is plenty of reasoning behind his opinions, I was very disappointed with this paper, which failed to change my opinions one whit. (To those of you not imbued with skepticism, hopefully I will now enlighten you.)

Yesterday I read a paper by the philosopher George E. Moore (pictured) called A Defense of Common Sense (full text). In the paper, Moore explains his view of the universe and talks about why he believes in the concept of common sense rather than extreme skepticism. Though Moore is an eminent philosopher and I am sure there is plenty of reasoning behind his opinions, I was very disappointed with this paper, which failed to change my opinions one whit. (To those of you not imbued with skepticism, hopefully I will now enlighten you.)To open his paper, Moore states that he is going to explain his philosophical view, specifically his opinions on common sense. He then rattles off a list of what he believes to truisms, such as his physical existence, other people’s physical existence, as so on.

But wait a minute—Moore is supposed to be disproving skepticism, particularly pyrrhonism (my brand of skepticism), why is he starting out by assuming realism? To truly disprove skepticism, he should start with no assumptions, like a skeptic does.

Moore then launches into a “proof” of common sense. This was not much of a proof at all—he simply applies simple logic to the assumptions he made in the beginning of the paper, and arrives at predictable conclusions. Nowhere does he truly prove common sense to be true. He does, however, use common sense as a tool to prove several of his assertions. He ends by criticizing philosophers whose answer to a question depends on the definition of the terms in the question, saying that everyone knows the definition of words because it is “common sense. ”

Who does he think he is convincing? Skeptics (such as myself), who are the very antipodes of people like Moore, would scorn this so-called “proof.”

To make this desultory rant even worse, Moore includes a small, entirely random section in which he states that he does not necessarily believe in God. He neither offers an explanation or proof of why he believes this nor discusses the implications of it. Again, who is he supposed to be convincing here? Not me, that’s for sure.

Finally, Moore explains his now famous “here is a hand” proof. Unfortunately, because the paper was written in 1925, Moore’s language is somewhat enigmatic and it is sometimes difficult to follow what he is saying. After reading it a few times, though, the message became clearer. Moore then asks if what we perceive is not real at all but simply bundles of “sense-data”—a question skeptics often ask. Moore’s conclusion is that although the sense-data we perceive may be somewhat different from the actual characteristics of the objects we are looking at (a hand, in his example), there is no doubt as to the definition of what we are seeing.

Again Moore uses common sense to back up common sense, and the proof only exacerbates his already flimsy argument against skepticism. Rather that proceed charily in his attacks on skepticism, he makes many bold (but unsupported) assertions.

To sum it up—this whole paper is nothing but a bombastic rant in which Moore chases his own tail. I remain unconvinced.

No comments:

Post a Comment